How do users know when they can trust what they encounter on the internet? A Crowe cybersecurity professional explains why asking specific questions about your chain of technology – and taking nothing for granted – is important.

When we travel alone in a busy, unfamiliar city, loved ones remind us to take extra safety steps, but on the internet, we often don’t receive the same cautions. When interacting with strangers in person, we are told that looks can be deceiving so we need to be wary, yet on the internet we seem to take information at face value.

Examples of misinformation on the internet are all around us. In 2019, PhishLabs reported that it encountered up to 25,000 phishing sites per month in recent years, accounting for millions of social engineering attack attempts. In the same time period, Twitter released information about more than 30 million tweets affiliated with a misinformation campaign from Russia’s Internet Research Agency and with other political movements designed to undermine discourse and that abuse Twitter’s terms of service.

Increasingly, the modern age of information seems to be transforming into the age of disinformation. In this evolving digital world, how can we reasonably trust what we encounter on the internet?

Blue checkmarks gone rogue

On July 15, 2020, Twitter was hacked via a combined social engineering and SIM-swapping attack that resulted in several high-profile accounts tweeting out a scam to receive bitcoin from followers. The tweet requested that users send money with the promise that it would be returned twofold. Alone, the message reeked of deception and even evoked memories of classic schemes such as the Nigerian prince advance fee scam.

The reason followers fell for the ploy is that they believed the message originated from the actual high-profile account owner because the tweet carried the trusted blue checkmark used to verify Twitter accounts. Twitter’s verification process includes having sufficient information on the profile, using a valid phone number and email address, providing links to other sites or profiles that corroborate an account, and providing an explanation for the account’s purpose. In some cases, copies of photo ID are even requested.

Several parody or troll versions of real accounts exist on Twitter, but the blue checkmark is what lets users know that an account is verified by Twitter as legitimate. In the case of the July 2020 hack, the accounts were legitimate, so the fooled followers trusted that the blue checkmark represented a legitimate tweet. Because they trusted the tweet, they might not have thought to evaluate the content of the tweet as potentially illegitimate, and some users experienced financial losses.

These types of implicit or misdirected trusts occur all over the internet. Had the blue checkmarks not been present, it’s possible that fewer people would have fallen for the scam. More important, though, this hack demonstrates how people blindly trust what they read on the internet based on a digital “legitimizer” that often is interpreted as an indicator of truthfulness.

Little green padlocks

When users navigate to a website, they’ll often see a (sometimes green) padlock next to the site’s URL in their web browser. What does that padlock symbolize? According to an informal poll in a 2018 report from PhishLabs, more than 80% of respondents said that they thought the green padlock indicated that a website was safe or otherwise legitimate. And why shouldn’t they? In Google Chrome, the most popular browser in the U.S., clicking on that lock presents a little box that states, “Connection is secure.” In Mozilla Firefox, the message displayed is “Secure Connection.”

What the PhishLabs respondents – and most users – might not realize, however, is that these messages are solely an indication of encrypted communications. In Chrome, the little box in the browser also states that “Your information…is private when it is sent to this site.” All this means is that the communication tunnel between the user and that site is encrypted, so outsiders will only see jumbled letters and numbers if they observe that traffic. The padlock has no bearing on whether the site or its content is legitimate.

Exhibit 1: Example of Google Chrome browser site information

Source: Crowe analysis

In its Q2 2020 report, the Anti-Phishing Working Group concluded that more than 75% of phishing sites now use HTTPS, meaning the padlock will appear next to their URL in web browsers. They use HTTPS for good reason: Chrome’s message for HTTP (unencrypted) websites is a triangular warning sign and a “Not secure” message, which would not be in an attacker’s interest. When creating phishing sites for simulated phishing exercises, penetration testers (like savvy attackers) use HTTPS encryption to protect the site and imply “legitimacy.” The reality is that anyone can get a certificate on their website that allows for this encryption; the only requirement is demonstrating the ability to post content on that website to prove ownership.

For the higher-tier extended validation (EV) certificates, the process also includes checking a provided address against popular directory listings as well as phone verification. However, this information can be faked (or more likely stolen) and aims to “verify” only that the business listed in the certificate exists and not whether the content is misleading or malicious. The authentication process aside, a certificate (EV or other) is intended only to lend trust toward the encryption of traffic to a website. Therefore, the padlock is another poor indicator of legitimacy, and in some cases it misleads users who are considering whether to trust a website and its content.

Another common phishing technique is to perfectly replicate popular websites and get users to visit by tricking them into thinking the websites are the real thing. If an email tells recipients to visit their Google accounts and then the link they click takes them to a site that looks exactly like the Google login page, they might have little reason to doubt what they’re seeing, despite the fact that the URL bar doesn’t say “accounts.google.com.” In reality, some ill-intentioned trickster has cloned the Google site and stood up a fake version on a website with a URL that looks close enough (maybe “accounts-google.com”). Similarly, individual graphics such as the Norton Secured seal can simply be added to a page to suggest to users that transactions and financial information are somehow secured or verified on the site, when in reality no such validation is occurring.

An informed mindset

So what does it mean to trust what is on the internet? Is there a balance between extreme paranoia and blissful ignorance? Certainly, a clear middle ground exists where users can explore the internet freely but still have an informed skepticism to avoid falling victim to scams. The key is understanding how trust plays a part in users’ participation in the internet.

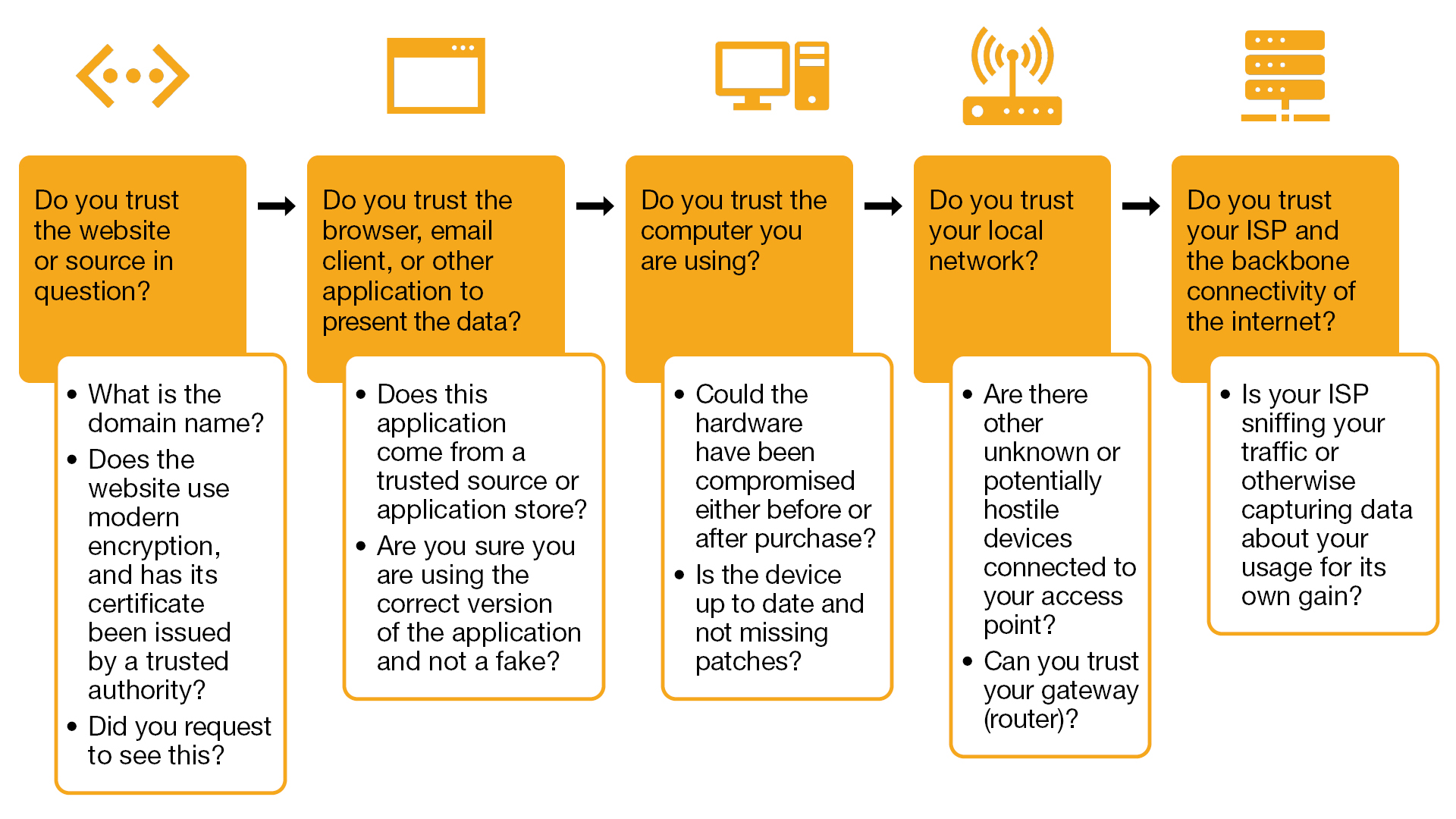

An informed mindset requires asking specific questions about trust for each link in the chain of technology that users follow as well as about the content itself. Users can work backward and determine how data moves from the origin point to their screens and, along the way, consider if at any point the information could have been manipulated or compromised.

The content of a website passes through many layers before it makes it to the end user. First, the content is created and uploaded to a web server. Then, once requested, it must traverse the internet and arrive at the user’s local network via the internet service provider (ISP). The local network then sends the information to the user’s device and presents it in an application. Theoretically, if compromise occurs anywhere during this process, what is presented could be at the mercy of someone with malintent and could be far from the truth.

For example, in a public location such as a coffee shop, an attacker in control of the Wi-Fi network could reroute a user’s traffic so that when she or he types in “accounts.google.com,” the attacker’s fake login page can be presented, despite the browser URL still saying “accounts.google.com.” In fact, a 2018 report from iPass claims that “free public Wi-Fi continues to pose the biggest mobile security threat for enterprises.” Additionally, “Of those respondents that had seen a Wi-Fi related security issue in the last 12 months, nearly two-thirds (62%) had seen them occur in cafés and coffee shops.”

To build trust in the content, users should ask themselves questions about the websites, browsers and other applications, computers, networks, and ISPs they are using.

Exhibit 2: Trust and the chain of technology

Source: Crowe analysis

For some of these considerations, users trust the websites and applications of large brand names and companies because they assume these brands and companies understand that subverting consumers’ trust and stealing their information or allowing others to do so is bad for business. The reality, though, is that for most of the chain of technology, users don’t have any control as individuals. Users are at the mercy of device manufacturers and ISPs. If a device were to be intentionally (or unknowingly) backdoored by a manufacturer, most device users would have no way of knowing. Similarly, if the ISPs choose to harvest information about browsing habits or otherwise tamper with connections, there is little that users can do to stop them. But what about the pieces that are within users’ control?

Building a web of trust

Developing a healthy skepticism based on an understanding of how technology is supposed to work and look is the solution. When in doubt, users should aim to understand the sources of information and the different parts of the technology chain that can verify those sources. Asking critical questions can help users determine whether they are the target of misinformation or misdirection. They can ask themselves:

- Does what I’m reading make sense, and can it be verified by an independent source?

- What is the intent of the presenter of this information?

- Did I seek this information or website out, or was it presented to me?

- What website am I truly on? What does the domain say?

- Could the connection I’m using be compromised, or am I using a known-good network?

- Is this my device or someone else’s? Can I trust that the device hasn’t been tampered with or otherwise compromised?

Put into practice, these questions can help guide users through many scenarios. Taking phishing as an example, a user can ask:

- Can I verify the content of this email based on other emails I’ve received?

- Does it link to a site I recognize and know to be trustworthy?

- Is this site asking for information from me? What is the intent of the site?

Say, for example, the email looks like a Google alert, claiming that the user needs to log in based on a security event:

- Can I verify on my phone or on another device if the same alert is communicated in a different way?

- Does the alert even make sense?

Similarly, if there is a payment request:

- Did I type in this website to get here? Or did someone send me a link?

- Do I want to enter my payment information on this device or network?

On the internet, trust is everything. That trust shouldn’t be a blind guess but rather a deduction rooted in what users can know and prove. Some links in the chain of technology can never be fully within users’ purview. But the important thing is to approach the information with a healthy skepticism and decide to trust it once its origins, presentation, and source are verified. If we take these steps, we can make the internet a safer place for everyone. Trust me.